The last time I wrote about an event organised by the Liverpool artist and poet, Maria Isakova Bennett, was in September 2019, in those pre-pandemic times that now seem touchingly innocent. Maria has now emerged from those troubling years with a new collection of poems that combines both her joy of words and her artist’s eye.

Painting the Mersey in 17 Canvases is dedicated to her father, Joseph, who “introduced me to the Mersey”, when he took her as a baby “to listen to the sound of the river”. She is still listening, as expressed in these lines from one of the poems, Coburg Wharf looking South and North:

listen to its slow churn

and wait for an accolade of water-stars

You can try to forget, but their pitch

will never leave you

Nick Branton and Maria Isakova Bennett.

Photo: Ron Davies

The 17 poems in this collection are short, pared down to the essence of what prompted their creation; on the printed pages there is space to breathe. At the launch of the book, she also inserted pauses, the reading of her work interspersed with extraordinary clarinet and saxophone improvisations by musician, Nick Branton. It was as if he had inhaled her poems and used the instruments to push out the sound of their rhythm, his cheeks and lungs filled with their meaning.

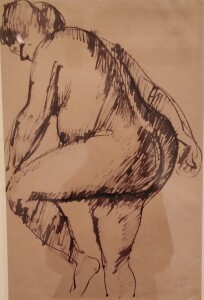

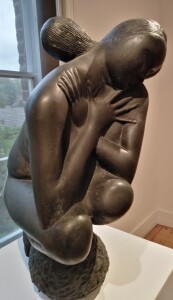

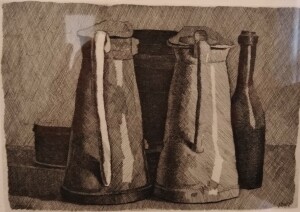

Visual artist, Michael Wright, who was also part of this gathering together of people from other art forms, keenly feels this connection between poetry and music. He regaled us with tales of his time as an art student in late 1970’s Liverpool, of the Mersey as a conduit, and casually passed around some of his evocative drawings from that time. But it was later on his website that I came across his essay on the intimate correlation between poetry, music and drawing: “Poetry has a musicality in its meter and rhythm which connects to the body rhythms, the pulse, the rhythm of breathing, walking, etc. The sounds, whether heard or iterated in the mind, generate a pitch and tonality to the poem. There is equally a correspondence between the process of mark making and the rhythms and pulses of the body. In this sense also there is some truth in the proposition that all art forms aspire to the condition of music”.

The evening began with readings from poets connected to Coast to Coast to Coast, the project Maria began five years ago, in which she publishes selected poetry in journals with unique stitched covers she has made by hand. For Maria, this return of the project after the long pandemic hiatus, was a poignant moment: “After more than two years, the event was full of hope and inspiration for art and creativity”.

The first to read was Carole Bromley, a prize-winning poet based in York. Her most recent collection, The Peregrine Falcons of York Minster includes the poem Bumping into John Lennon, the closest, she said, with a Liverpool connection. It includes the following witty and incisive lines:

Once or twice he crept into the back

of Macca’s concerts but, to be honest,

couldn’t take the hair dye, the terrible lyrics.

The last time I saw him

he was up a ladder fixing a pane,

whistling Maxwell’s Silver Hammer.

Next up was Barbara Hickson, whose poems focus primarily on our relationship with nature and place, intensely evident in her recently published collection, A Kind of Silence. This includes the poem Succinct, which emulates its title:

It’s easy to talk

yet say nothing.

In the woods behind Witherslack

we startled five deer.

They stood – fixed, staring –

then sprang away

clearing the fence effortlessly.

They told us everything

we didn’t want to know.

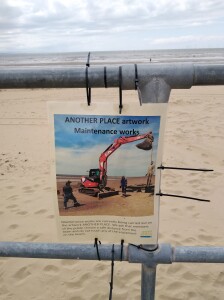

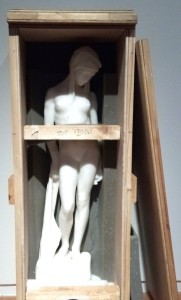

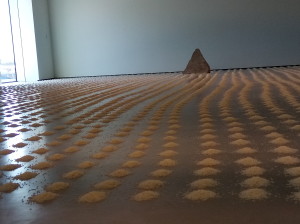

Antony Gormley’s “Another Place”, Crosby Beach

Photo: Ron Davies

A regular presence at Maria’s events is Crosby-based photographer, Ron Davies. On this occasion, he not only took photos but also gave a presentation of some of his archival images. He spoke of how Maria’s poetry had inspired him to re-look at his own work, some of which “hadn’t seen the light of day for many years”.

Painting the Mersey in 17 Canvases is published by Hazel Press. Maria expressed her delight at being invited by a company with such strong eco credentials and especially that they had chosen the world-renowned illustrator, Jeff Fisher, to design the cover. For their part, Hazel Press are proud to have her as one of their writers: “these poems ‘paint’, observe and illuminate the permanence and maybe of life on and beside a river full of flow and stillness, solace, surprise and permanence; they return, again and again, to redraw a sense of place and self that, like the river, is ever-changing”.

Maria Isakova Bennett reading.

Photo: Ron Davies

Wall images by Etinosa Yvonne

The Open Eye Gallery was host to the launch evening, an appropriate setting given its proximity to the Mersey, and the title of its present exhibition – Follow the River, Follow the Thread – sent an echo from Africa about our vital connection to water. The series of diptych images in the gallery where we were seated are by documentary photographer, Etinosa Yvonne, from Benin, Nigeria. They show everyday routines of people sourcing clean water that at first seemed an incongruous backdrop to this event, but gradually their presence seemed to evoke an exchange of bearing witness to human endeavour and creativity.

I was struck more than anything after this celebratory evening of the arts, of how deeply a place can take root if a person stays long enough. Maria’s poems pour love back into the Mersey, the river that has inspired and nurtured her. The last poem in this new collection exemplifies this:

Where the Mersey reaches the Sea

I was born close to you

and when I lose all sense of me

I hug your waterline

There is no distinction between us

I am and you are

Some people sit in silence

and wait for God

I listen to your roar

note sanderlings

their nervous necessary dance