It felt like being in the opening sequence of a Scandi-Noir TV series – driving in the dark into a badly lit, empty industrial street, closed up old buildings all around, my car tyres crunching over litter in the gutter … the scene heightened by a single red light bulb hanging over a set of new wooden steps, which lead to a black curtain over a doorway. This, though, was definitely my destination – one of the 19th century warehouses across the road from the new, emerging Everton football stadium. The parting of the black curtains perpetuates the surreal sense of theatricality but then once inside there is, unexpectedly, the familiar scene of an exhibition opening event, still so welcome after the dearth of the pandemic years.

It felt like being in the opening sequence of a Scandi-Noir TV series – driving in the dark into a badly lit, empty industrial street, closed up old buildings all around, my car tyres crunching over litter in the gutter … the scene heightened by a single red light bulb hanging over a set of new wooden steps, which lead to a black curtain over a doorway. This, though, was definitely my destination – one of the 19th century warehouses across the road from the new, emerging Everton football stadium. The parting of the black curtains perpetuates the surreal sense of theatricality but then once inside there is, unexpectedly, the familiar scene of an exhibition opening event, still so welcome after the dearth of the pandemic years.

The artists are aware of how it will all seem, pre-empting in their catalogue with self-deprecating humour what visitors may be feeling: “… you have made a pilgrimage to the north of the city centre, to a landscape possibly unknown to you, perhaps with understandable trepidation. Fear not. The environs of this warehouse are sacred ground, the sanctuary boundary is voiced in stone, brick and even by name. The temple is a place of refuge”. The temple in question here is the re-imagining by artists, Adrian Jeans and John Elcock, of this historic Liverpool dockland warehouse as a Greek temple. It’s a stretch of the imagination but holding onto their artistic conceit acted as a guide, especially given that there are no curatorial explanatory wall notes – a bonus in my view, and Jeans and Elcock are only too eager to engage with viewers about their responses to the artworks.

This connection with the viewer is what Elcock says he has been craving all through the long solitary months of lockdowns and restrictions; the ghost of Duchamp’s assertion hangs in the air as we talk – that it is the viewer who completes the artwork. It reminds me too of something the sculptor Phyllida Barlow said in a recent radio interview: “There’s plenty of art that’s never seen. And I’m intrigued by that, making work that does not have a destination, has a sadness and loneliness about it. Many artists endure that for their entire lives and it’s heroic”.

This connection with the viewer is what Elcock says he has been craving all through the long solitary months of lockdowns and restrictions; the ghost of Duchamp’s assertion hangs in the air as we talk – that it is the viewer who completes the artwork. It reminds me too of something the sculptor Phyllida Barlow said in a recent radio interview: “There’s plenty of art that’s never seen. And I’m intrigued by that, making work that does not have a destination, has a sadness and loneliness about it. Many artists endure that for their entire lives and it’s heroic”.

For a minimalist exhibition in terms of actual pieces, there’s a lot to absorb here. Even the title “Present Perfect Progressive Tense” stretches the brain back to school English grammar lessons. The artists have kindly provided a definition – it is a verb form indicating that something was happening and is still happening. Jeans and Elcock have chosen it because the same tense applies to them and their contemporary works, which directly reference the ancient world.

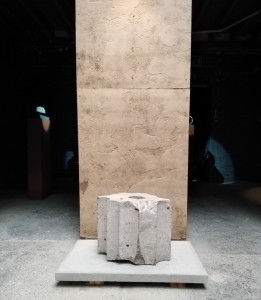

Elcock’s work was presented at the back of this cavernous space, in a kind of darkened inner sanctum. The handful of  what resemble sacred objects are reverentially lit, exquisitely mounted, the plinths carefully spaced so there is room to move around them and to examine them closely. They are all found objects, as diverse as a sheep’s head and a chunk of asphalt, their essence transformed and presented back to the viewer in such a way as to evoke precious fragments saved from oblivion. Elcock explains: “I am really into the symbolism of objects, the affects and meaning of materials … everything has meaning. I am a hoarder”. Later that evening after speaking to him, the following sentence leapt out of the book I was reading, John Banville’s “Snow”: “The dullest object could, for him, flare into sudden significance, could throb in the sudden awareness of itself”.

what resemble sacred objects are reverentially lit, exquisitely mounted, the plinths carefully spaced so there is room to move around them and to examine them closely. They are all found objects, as diverse as a sheep’s head and a chunk of asphalt, their essence transformed and presented back to the viewer in such a way as to evoke precious fragments saved from oblivion. Elcock explains: “I am really into the symbolism of objects, the affects and meaning of materials … everything has meaning. I am a hoarder”. Later that evening after speaking to him, the following sentence leapt out of the book I was reading, John Banville’s “Snow”: “The dullest object could, for him, flare into sudden significance, could throb in the sudden awareness of itself”.

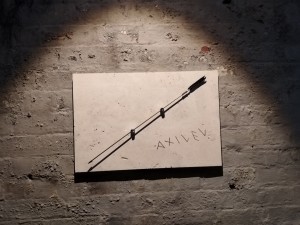

The one wall-mounted piece amongst Elcock’s objects is perhaps the clearest example of a link to Classical times. It is a tiny 4th century BC Greek bronze arrowhead purchased from an antique dealer, which he has completed with a slim brass tube for the arrow shaft, a crow’s feather for the fletching, tied on with a length of old string. It is mounted on marble with an etched tribute to Achilles, a fighting hero from Greek mythology. Standing guard outside Elcock’s sanctum is what looks like a section of an ancient Greek Corinthian pillar, but which turns out to be one of his found objects. It is in fact a sizeable chunk of concrete from the demolished Churchill Way flyovers at the end of Liverpool’s Dale Street. Half a century ago, the Concrete Society gave the flyovers their annual award, their highest accolade. Until Elcock’s repurposing of this piece of it, that was about the pinnacle of the praise the Churchill Way ever received.

Jeans’ work was sparingly placed around the front half of the artists’ Temple, this warehouse, which, to quote again from their catalogue “is in itself an expression of a persistence of form, a structure that has continued to adapt to the ebbs and flows of this port city”. The first objects you see are Jeans’ casts of four sculpted heads, lolling dramatically at different angles on a low plinth, almost on the ground, spewing out different coloured latex. A hand-painted poster, an artwork in its own right, provides an explanation for the heads. They are a 3-D manifestation of the Platonic Humours, the classical theory that the body was made up of four main components. These needed to remain balanced in order for people to remain healthy. The Four Humours were liquids within the body – blood, phlegm, yellow bile and black bile.

Jeans’ work was sparingly placed around the front half of the artists’ Temple, this warehouse, which, to quote again from their catalogue “is in itself an expression of a persistence of form, a structure that has continued to adapt to the ebbs and flows of this port city”. The first objects you see are Jeans’ casts of four sculpted heads, lolling dramatically at different angles on a low plinth, almost on the ground, spewing out different coloured latex. A hand-painted poster, an artwork in its own right, provides an explanation for the heads. They are a 3-D manifestation of the Platonic Humours, the classical theory that the body was made up of four main components. These needed to remain balanced in order for people to remain healthy. The Four Humours were liquids within the body – blood, phlegm, yellow bile and black bile.

A nearby alcove has been stuffed with dozens of hands cast in different coloured plaster, all severed just below the elbow. Up close it’s clear that there is a variety of different gestures and Jeans explains that he has culled these not only from antiquity but also based them on hands from contemporary artworks, newspapers, magazines and gesticulating people he sees in the street. What I hadn’t noticed is that they are all of a left hand, the reason for this being that Jeans has modelled them all from posing his own hand, using his dominant right hand to make the sculptures. He has mounted one of these hands on a rotating plinth – the gesture is a V sign, which changes its message from Friend to Foe as it slowly turns. Jeans explains how this on-going investigation of gesture is important to his art practice: “A sculpted head is a static portrait whereas hands are more expressive and talk. They’re a different way of focussing on the portrait sculpture tradition, and of exploring the perceptions of ourselves and of others”.

Up close it’s clear that there is a variety of different gestures and Jeans explains that he has culled these not only from antiquity but also based them on hands from contemporary artworks, newspapers, magazines and gesticulating people he sees in the street. What I hadn’t noticed is that they are all of a left hand, the reason for this being that Jeans has modelled them all from posing his own hand, using his dominant right hand to make the sculptures. He has mounted one of these hands on a rotating plinth – the gesture is a V sign, which changes its message from Friend to Foe as it slowly turns. Jeans explains how this on-going investigation of gesture is important to his art practice: “A sculpted head is a static portrait whereas hands are more expressive and talk. They’re a different way of focussing on the portrait sculpture tradition, and of exploring the perceptions of ourselves and of others”.

Jeans echoes Elcock’s earlier comment about the importance of the viewer’s response to an artwork. For Jeans it is akin to the triumvirate of ancient Rome –“there is the relationship between the model and the artist, which is then interpreted by the viewer”. On a nearby wall, Jeans has mounted four identical sculpted heads. Each is adorned with a different headdress to represent the Four Faces of Religion – Atheism, Monotheism, Polytheism and Animism, all known in ancient times. The face is a sculpture that links Jeans back to his own past when his art practice took him to Ghana, straight after graduating from Glasgow School of Art. It is a sculpted portrait of R.T. Ackam, Associate Professor at the art college in Kumasi, the capital city of the Ashanti Region, in southern Ghana. The Four Faces of Religion was Jeans’ proposal for Liverpool’s  Princes Avenue empty plinth. This would have the four heads joined together to face the four different places of worship that surround the site – a Greek Orthodox church, a Mosque, an Anglican Church and a Synagogue. On the opposite wall are delicate paper cutouts of the different religious headdresses. Jeans is rather casual about the skill involved in making these, saying they are just like the snowflake cutouts he used to make as a child with his mother and grandmother. They are also act as an art historical link to the once popular practice of silhouette cutouts.

Princes Avenue empty plinth. This would have the four heads joined together to face the four different places of worship that surround the site – a Greek Orthodox church, a Mosque, an Anglican Church and a Synagogue. On the opposite wall are delicate paper cutouts of the different religious headdresses. Jeans is rather casual about the skill involved in making these, saying they are just like the snowflake cutouts he used to make as a child with his mother and grandmother. They are also act as an art historical link to the once popular practice of silhouette cutouts.

I was intrigued to know about the choice of a red light at the entrance to the show. Their different responses reflect the quiet humour at the heart of this show. Jeans’ explanation: “We installed the red light outside so as to visually differentiate our ‘temple’ building from the more prosaically used properties around it and, in addition to the black curtain, add a little theatricality to the experience of visiting the exhibition. It also works as an acknowledgement of the less salubrious reputation of the dockland area”. And Elcock: “The red light refers to our ambition to imagine the space as the sanctuary within a wider temple precinct. The light guiding pilgrims, as in the classical era, for those who have made the journey up into the north docks”.

These two artists certainly proved that this 19th century Liverpool warehouse is, as they claim, a building capable of housing contemporary art with the same élan as piles of old tyres or a cask of molasses.