In all the time I have spent walking Crosby Beach in the company of Antony Gormley’s iron men, I hadn’t noticed that a few of the 100 figures were missing; no, not stolen, but keeled over and sunk deep into the black, quicksand mud, their concrete plinths having decayed. Powerful metal detectors had to be used to find them, as they were no longer in the same location of their original GPS coordinates. When they were pulled from the mud, they looked more like the images of preserved bog men from centuries ago. But these iron men have only been in place for 16 years, though Gormley hopes they will still be around for at least a thousand years, gradually eroding to resemble Giacometti’s skeletal sculptures.

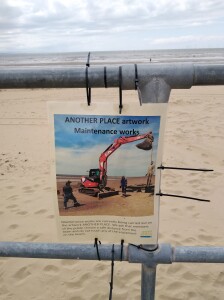

They were recovered during recent maintenance work, in which 50 of the figures at the Port end of the beach were removed so that new plinths could be made.

They were recovered during recent maintenance work, in which 50 of the figures at the Port end of the beach were removed so that new plinths could be made.

When the figures are in situ, especially those far out to sea, they can give one a heart-stopping moment as waves crash over their heads. We are hard-wired to immediately think someone is in trouble. Even being familiar with the presence of the iron men, it can sometimes take a few seconds for the scene to be understood.  A similar human response to the figures came on seeing so many of them laid out flat on their backs.

A similar human response to the figures came on seeing so many of them laid out flat on their backs.

This time the emotional disturbance was because they resembled bodies lined up in a makeshift morgue; laying them flat had dissipated their power – something iconoclasts have always known and a current example of which is the Edward Colston statue, toppled last year during Bristol’s BLM protest. It now lies supine in the M Shed Museum in Bristol while its future is decided.

Gormley himself has been in Crosby overseeing the restoration of the figures and whilst not wanting to disturb him for too long when he was busy doing something very important with a theodolite, I did manage to ask him a couple of questions – whether it was just the plinths being replaced and whether all the entropic effects on the steel were to be retained? “Oh yes”, he confirmed, “every barnacle is precious. Only the plinths are being replaced”. In the The Guardian interview he contradicted this but not to worry, barnacles are tenacious creatures so they’ll soon be back if they were cleaned off.

Whilst all the work was going on, pillars were placed to mark where each figure  had stood and it was interesting how these temporary objects seemed to retain some of the presence of Gormley’s men, like sentinels guarding their positions. This also has an echo in the story of the Colston statue in that the empty plinth resonates with its history – recent and past. People come to see it, recognising its emptiness as a symbol of an historic moment, in the same way as thousands queued to see the empty space where the Mona Lisa had hung after it was stolen from the Louvre in 1911.

had stood and it was interesting how these temporary objects seemed to retain some of the presence of Gormley’s men, like sentinels guarding their positions. This also has an echo in the story of the Colston statue in that the empty plinth resonates with its history – recent and past. People come to see it, recognising its emptiness as a symbol of an historic moment, in the same way as thousands queued to see the empty space where the Mona Lisa had hung after it was stolen from the Louvre in 1911.

Meanwhile, back on Crosby Beach, all 100 of the iron men from Another Place are now back in place, all facing West, all at the same horizon plane, all waiting for time and tide.