The approach by road to the Hepworth Wakefield goes through an unpromising industrial area. But once there and you start up the walkway to this 2017 Museum of the Year, it becomes obvious why the location was chosen. The contemporary concrete and glass design by David Chipperfield Architects sits on the city’s historic waterfront overlooking the River Calder. The positioning of the building stunningly exploits the vista from both outside and in.

Until the end of September 2019, the Museum is one of four venues making up the Yorkshire Sculpture International, the others being the Yorkshire Sculpture Park, the Henry Moore Institute, and Leeds City Art Gallery.

So far I’ve only been to the Wakefield and the work that appealed to me the most was by Iranian-born, Nairy Baghramian, who lives and works in Berlin. Here, she combines four material elements: large, rough sheets of raw aluminium casts, pastel-coloured wax forms and lacquer painted industrial clamps with cork.

who lives and works in Berlin. Here, she combines four material elements: large, rough sheets of raw aluminium casts, pastel-coloured wax forms and lacquer painted industrial clamps with cork.

The way she uses the braces to lean two contrasting slabs towards each other evokes a figurative, human tenderness. I spent ages in this gallery, enjoying how she uses space and light in the forms, as well as the contrast and juxtaposition of the edges – the softness of the wax nearly touching the ragged edges of the aluminium casts. The apparent permanence of the wax form is an illusion because, of course, if the polishing were repeated ad infinitum, the form, despite its size, would eventually disappear.

The way she uses the braces to lean two contrasting slabs towards each other evokes a figurative, human tenderness. I spent ages in this gallery, enjoying how she uses space and light in the forms, as well as the contrast and juxtaposition of the edges – the softness of the wax nearly touching the ragged edges of the aluminium casts. The apparent permanence of the wax form is an illusion because, of course, if the polishing were repeated ad infinitum, the form, despite its size, would eventually disappear.

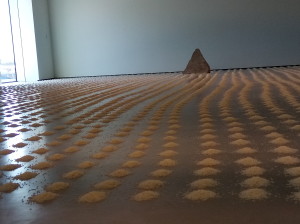

Repetition is a key element in Wolfgang Laib’s installations; he regards it (repetition) as “the most beautiful thing that exists.” This idea is connected to the Buddhist and Hindu philosophy that there is no beginning and no end, that there is an eternal recurrence of the same. Laib sees his work as a process of participation with his materials, which are usually organic, living substances – beeswax, milk, pollen, and rice. As sculpture, he says, they make a “field of energy”, concerned, as is all his work, not with creation but “the search for an entrance or a passage to another world.”

In Laib’s new installation at the Wakefield, Without Space – Without Time – Without Body, rice is the key element that Laib wants to act as the conduit to this other realm.  There are hundreds of little mounds of it laid out in a grid that fills the gallery, interrupted by a few pieces of roughly hewn, ash-covered granite, that have echoes of ancient tombs.

There are hundreds of little mounds of it laid out in a grid that fills the gallery, interrupted by a few pieces of roughly hewn, ash-covered granite, that have echoes of ancient tombs.

I was looking forward to seeing this installation, being drawn to some aspects of Buddhist philosophy and also to minimalism in visual art. However, I realised once I stood before it that I am ambivalent about food being used in art. Perhaps because of this I couldn’t quite believe that this work lived up to Laib’s creed that art is a form of “transcendent spiritual healing and sustenance”. That said, it has set me off on a path of examining the history of food and art, of exploring the morality of it and of attempting to understand the artists’ motives.

This Museum is named after the sculptor Barbara Hepworth, who was born and brought up in Wakefield. It is a magnificent space for her work, with even the largest of her pieces having room to boast its monumentality. There are also dedicated galleries exploring Hepworth’s art and working process. Plus, the Museum is home to Wakefield’s impressive collection of works by other modern British artists, among them Ben Nicholson, Patrick Heron and Henry Moore. In addition, it has works by significant contemporary artists such as Frank Auerbach, Maggi Hambling, and Eva Rothschild, all of which are frequently on show, some permanently.

It is a joy to spend time in this Museum at any time but especially so for the next few months with this rare opportunity to see such a wide range of sculpture, some of it specially commissioned for this Festival.