On Crosby Beach there is a tractor driver whose job it is to scoop up the sand that has encroached on the coastal paths and deposit it back on the beach. Each day the wind and tide move it inland again. Every time I see him at work, it puts me in mind of the Greek mythological legend of Sisyphus, which is, of course, a metaphor for the futility of so many things in life. He was condemned to repeat into eternity the task of pushing an immense boulder up a hill, only for it to roll down again when it nears the top. The parallel of trying to hold back the sand on the beach is obvious; and yet, as with a lot of daily chores and tasks that have an endless cycle of repetition, without them being carried out chaos could easily ensue. And I suppose that at least this one has the benefit of being carried out in a beautiful location.

On Crosby Beach there is a tractor driver whose job it is to scoop up the sand that has encroached on the coastal paths and deposit it back on the beach. Each day the wind and tide move it inland again. Every time I see him at work, it puts me in mind of the Greek mythological legend of Sisyphus, which is, of course, a metaphor for the futility of so many things in life. He was condemned to repeat into eternity the task of pushing an immense boulder up a hill, only for it to roll down again when it nears the top. The parallel of trying to hold back the sand on the beach is obvious; and yet, as with a lot of daily chores and tasks that have an endless cycle of repetition, without them being carried out chaos could easily ensue. And I suppose that at least this one has the benefit of being carried out in a beautiful location.

Away from such philosophical musings, I recently had the pleasure of going to Manchester’s City Gallery for the first time. It is another of the majestic buildings, in which the North West of England is so rich. I went to see a sculpture exhibition, Out of the Crate, which turned out to be a real gem.

Away from such philosophical musings, I recently had the pleasure of going to Manchester’s City Gallery for the first time. It is another of the majestic buildings, in which the North West of England is so rich. I went to see a sculpture exhibition, Out of the Crate, which turned out to be a real gem.

The aim of it is to provide the viewer with an opportunity to investigate sculpture through access to stored collections and archival material. It has been set out over three rooms so that it is part exhibition, part storage room and part research space. There are works in a wide range of materials, including marble, bronze, wood, glass, ceramic and paper, in a variety of sizes and shapes and different techniques of making.

archival material. It has been set out over three rooms so that it is part exhibition, part storage room and part research space. There are works in a wide range of materials, including marble, bronze, wood, glass, ceramic and paper, in a variety of sizes and shapes and different techniques of making.

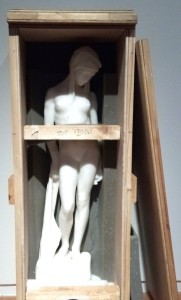

Seated Youth by Alfred Stevens

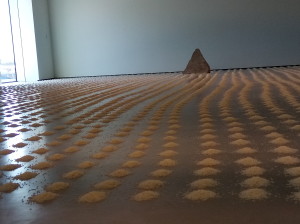

Like most galleries and museums, the City Gallery has a large collection of works that have rarely been seen this century. Less than 3 percent have been on display but with this exhibition there is a chance to see a quarter of the 500 sculptures in the collection. It is like being given privileged access to the storeroom. Objects are displayed on industrial racks, in glass-fronted cupboards, on pallets and in open crates. They are grouped according to size and/or material and weight. This is in contrast to the conventional gallery display when the curators are more usually guided by themes or chronology.

Nude by Henri Gaudier-Brezska

One of the first sculptures one comes upon is Rodin’s Portrait of Victor Hugo. It is almost more powerful to see it contained in a crate, heavily strapped in, as if it were the only way to control its immense energy. All the big names are here, ranging from antiquity to the present day. There are also works by several sculptors I hadn’t heard of before, among them Alan Lydiat Durst, Elizabeth Andrews and Maria Petrie. The latter’s Portrait Study was one of my favourites, but if I’d had to choose one to take home with me it would have been Henri Gaudier-Brzeska’s Nude, a beautiful small study in white marble.

There are several excellent examples of work by Alfred Stevens, the British sculptor born into the 19th century but who lived through modernist era to 1970. Barbara Hepworth’s Doves are touching in their simplicity and tenderness and reminded me of the pair of collar doves that frequent my garden. One of the most affecting scenes was to see one of them put its wing around the other as if in a loving embrace.

The research room has been set up like a detective’s cold case crime scene, with sculptures about which little is known under investigation. The public’s help is sought here in helping the gallery find out not only the provenance of the pieces but in some cases the artist and/or the sitter. In opening up this research process more publicly, the aim is also to consider how a public gallery and its users can care for and use collections.

I spent so long in this exhibition, thrilled to find such an eclectic collection of sculptures on display, that I only had time for a quick look at the rest of the gallery. Ho hum. I’ll just have to go back, which I can definitely say will be no great hardship.