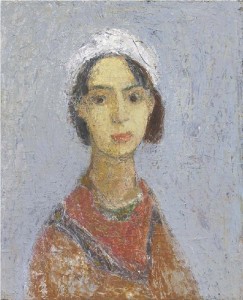

Russian artist, Gennadii Gogoliuk, reciting poetry in his Edinburgh studio. (Click on image to enlarge).

On meeting the artist, Gennadii Gogoliuk*, at his Edinburgh home, he hands me two of his sketchbooks before heading out the door to buy breakfast for us. As he leaves, he calls out something in Russian and his wife, Rose**, translates: “He says that sketchbooks are where the heart of the artist lives”. I know this; I recognise the privilege of being given them to look through. It’s nerve-wracking setting them down on the kitchen table, too close I think to my cup of tea – the more so when Rose tells me that these are books that Gena has re-worked over and over for the past ten years. They are extraordinary; the pages heavy with paint and history. Spasmodically interrupting the painted pages is the added dimension of the, to me, unfamiliar calligraphy of the Russian language. The books are palimpsests of Gena’s cultural heritage and of his continuous creative process. One little painting has the look of a monotype but it turns out to be what has bled through from the other side of the page, the original now obliterated by other figures from Gena’s imagination. He comments that the beauty of this unintended image lies in the fact that it is “untouched by human hand, that it has made itself”. This attributing of his art to something ‘other’ becomes a recurring thread in our conversation. He talks about his process as taking place when he is not present, in the sense that when he paints, he disappears into some other part of himself. He describes this loss of himself as “the joy of painting”, that it is a “magical profession”.

The London gallery owner, John Martin, saw Gena’s work at a group show and invited him to put on his first solo exhibition in 2001. Rose recalls how important and fortuitous this was for Gena, especially when it came so soon after his move from Russia in 1998 to be with her in Edinburgh, her home city. The show was well received and others at the gallery have followed. He has also exhibited at the Royal Scottish Academy and the Society of Scottish Artists. For Gena, there is the artist’s eternal dilemma between wanting/needing his work to sell and then being conflicted that gallery success might influence the type of work he makes. He describes the instant a painting dies for him if the thought enters his head of how it will be viewed by others. “That’s the moment of death”, he says, with a dramatic gesture of his hands.

Later, when we go to his studio there is a painting on the easel of a fish on a plate. In subject matter, it is quite unlike any others there, which are mostly of faces and figures. Gena isn’t sure about it, isn’t sure if it is finished or not. The proverbial artist’s doubt is fully alive in him. He describes how he used to know when a painting was finished, when it was ready to go out into the world, because he had a strange taste like blood in his mouth. Now, he says, he doesn’t have any such tangible indication; to paraphrase Descartes, it is the doubt that keeps him seeking the truth of the painting.

The studio is small, the view from the window of the railway track to nearby Haymarket. Stacked all around the room are paintings of varying sizes and in various stages of execution. There is an undercurrent of things going on in his paintings; the faces in the portraits only revealing a fraction of their story – of his story … “because everything I have ever looked at or experienced is in my paintings”.

He has been trying out some different ideas, such as painting on photographs; others are on brick-size, gesso-covered canvases. Our talk is more halting now because Rose, our translator, has left us to pick up the youngest of their three daughters from school. The performer in him takes over to occupy the spaces in our conversation and he declaims one of his poems. It seems irrelevant that I can’t understand the Russian and Gena is not really able to explain its meaning in English. The speaking of the poem is what is important. (I should add that Gena does speak English but with Rose present the conversation clearly has more of a flow when he is expressing himself in Russian. English is the main language in their family home).

In one corner of the studio there is a heart-breakingly simple shrine, where Gena has a ritual of lighting a candle in front of a battered Russian icon. Before lighting the candle, he paints a tiny symbol on it. He knows that the candle will burn for six hours and he keeps himself in the studio until the flame dies – not always painting, sometimes gazing unseeing at the canvas he has prepared with gesso, waiting for what wants to be painted to reveal itself.

I comment on the white “veil” he often paints over his subjects and ask if this is related to the spiritual aspect that is sometimes attributed to his art. But he says not, that it is all to do with his desire to capture the essence of old and crumbling frescoes. “I prepare the canvas with layers of gesso to make it like a wall, like plaster that will absorb the paint so that there is a beneath and an above”. In this he recalls the legendary mediaeval Soviet icon painter, Andrei Rublev. This in turn leads to his recommendation of the film by Soviet film-maker, Andrei Tarkovsky, which immortalised Rublev’s peripatetic life as a wandering artist and man of faith.

Our conversation turns to the contrast between Russia and Britain in the status the artist is accorded– or at least as it was in the former Soviet Union – that during his formative years, artists were an elite, needed for official (political) art, such as statues and monuments. Once the Soviet system began to fall apart in the 1990’s, artists became less important. It was during this period of flux, particularly with the advent of perestroika and the lifting of censorship, that Gena became increasingly involved in conceptual and avant-garde art. Prior to this he had been studying at the St Petersburg Academy of Art, where his early experimental work brought him into conflict with their neo-classical style and technique. Gena was thrown out of the Academy several times before he was eventually permitted to present a diploma painting that allowed him to graduate in 1990.

Although painting now largely dominates his art practice, evidence of performers pepper the canvases. He sees his paintings as inextricably linked to his work as a performance artist and not constrained by his Academic training. He still finds an outlet for his theatrical talents, most recently in a film made in Germany through collaboration with a group of dancers who specialise in improvised movement. It featured him dressed in a feathery Pan outfit – the mythological figure being one of his frequently revisited symbols.

Gena’s art influences are wide-ranging, from the colourful cut-outs of Matisse to fellow Russian, Malevich and his world-famous, “game-changing” Black Square. It was fascinating to hear from Gena, a compatriot of Malevich’s, just how important the painting has been to artists in Russia – that over the years its very existence gave them courage to go forward with new forms of expression.

As well as being represented by the prestigious John Martin Gallery in London, Gena also had the honour of being included in the collection of art connoisseurs, the late Professors Henry and Sula Walton. Their patronage has led to Gena’s paintings “rubbing shoulders” with work by heavyweights such as Goya, Rembrandt, Cezanne and Picasso. The couple, who had lived in Edinburgh for many years, bequeathed their collection to the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art. In a short film about Gena, Henry Walton, described how he felt that Gena “is embedded in his Russianness, to his personal detriment but to the great enrichment of his art”. I ask what Professor Walton meant about the effect on him personally of his Russianness and both Gena and Rose allude to the unruly force of his Russian heritage and of the struggle to allow it expression without being dominated by its darker side.

In one of her BBC Reith Lectures the author, Hilary Mantel, spoke of the “tension in every artist between the outer and inner lives. You want to be at your desk or in your studio, mining your resources, but you also want to be out there in the world, listening and looking, to replenish your talent. There’s no safe point, no stasis. It produces anxiety, even a kind of shame”. I feel Gena would relate to this description of the artist’s creative process.

We had sat for a couple of hours in Gena and Rose’s kitchen, drinking tea, eating croissants, the conversation meandering between art and philosophy and back again. The flow of talk was facilitated by Rose’s impressive ability to translate Gena’s Russian, whilst also contributing her own insights . Listening and talking to them was a rare and nourishing experience, like food for the soul.

* Gennadii Gogoliuk was born in Sholkhov, Rostov Oblast, Russia in 1960. He studied at the Lugansk art school in the Ukraine and later at the St Petersburg Academy of Art. He worked for several years with the Kirov Theatre (now the Mariinskii Theatre) in St Petersburg.

**Rose France is a Teaching Fellow at the University of Edinburgh’s Russian Section of the Department of European Languages and Cultures, and the School of Literature, Languages and Cultures.